Just days before the Spring Meeting of the World Bank Group and International Monetary Fund (IMF), the UN’s climate chief Simon Stiell issued a stern statement to global finance leaders, reminding them that the world does not have time for empty agreements. He’s right: if the rate of warming continues to accelerate, as it has in the last two years, the planet will be 1.5°C warmer within a decade and 2°C warmer by mid-century on average. Historically, the kind of “quantum leaps” Stiell is asking for have come from close collaboration between governments and philanthropists who have been at the forefront of international climate mitigation efforts.

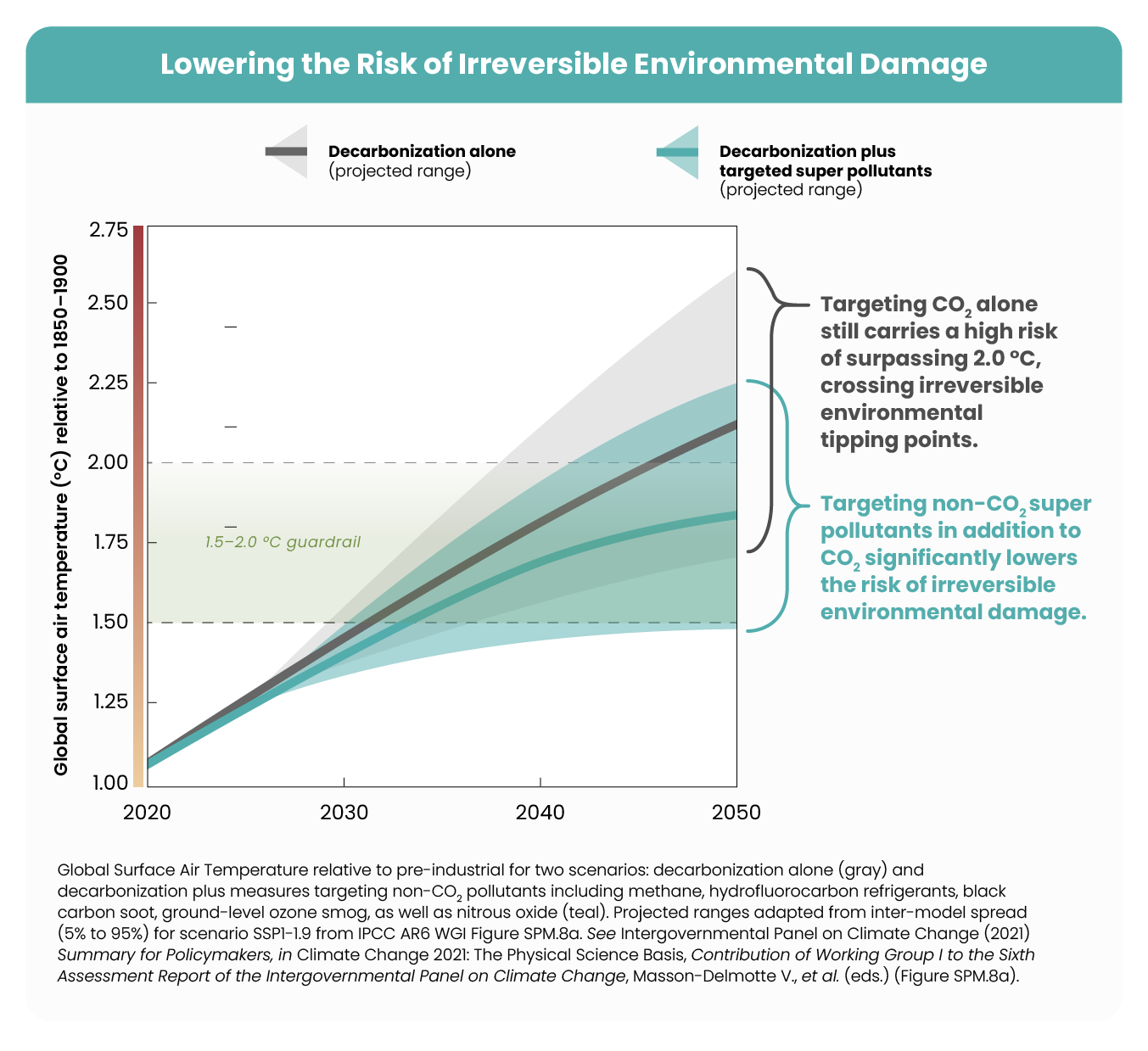

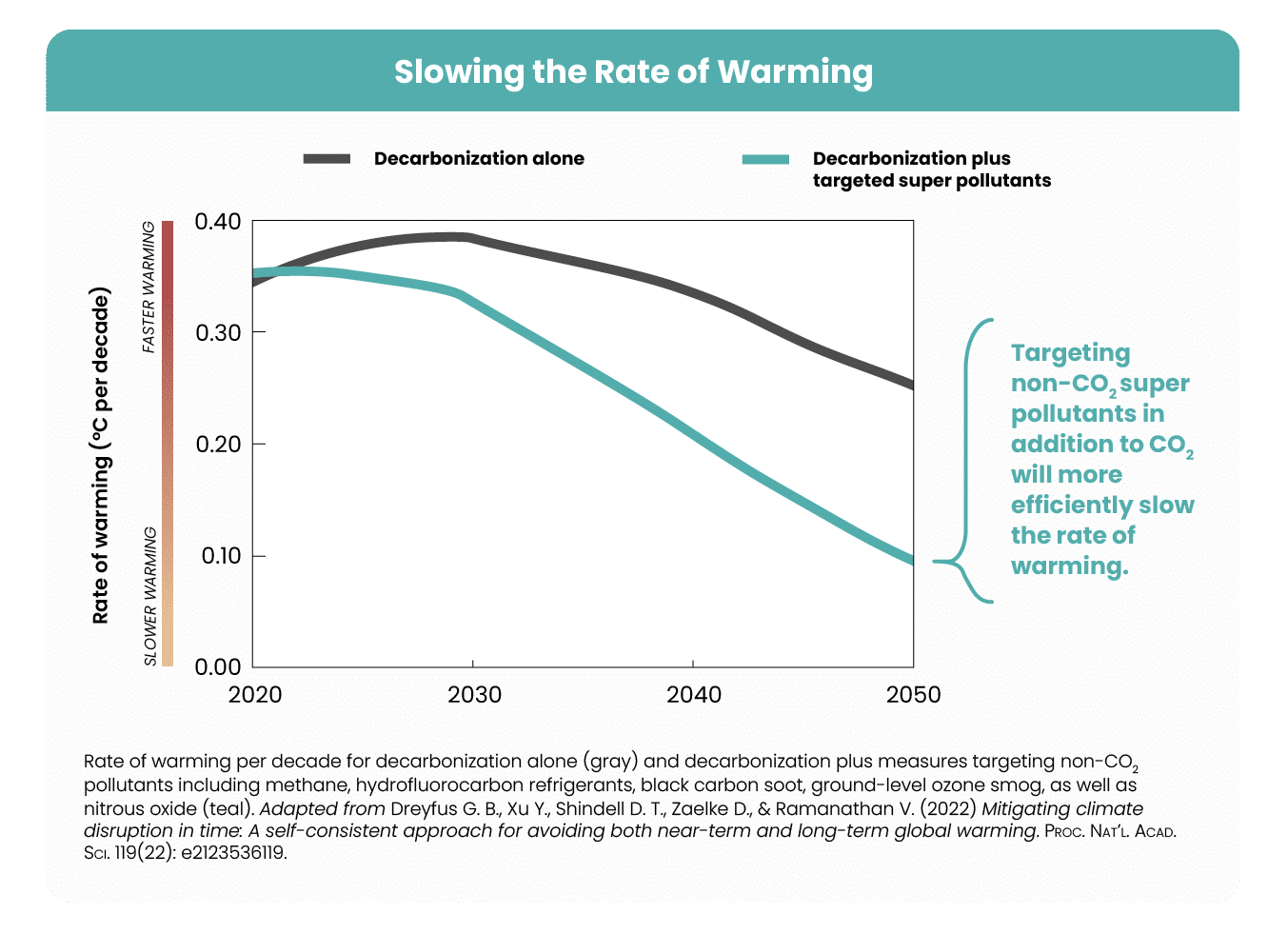

With little time left to slow warming, philanthropy, long supportive of efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, is stepping up efforts to deepen its investments in other more potent climate pollutants. Cutting “super” climate pollutants alongside continued efforts to decarbonize economies can slow warming four times faster than focusing on carbon alone. Building on recent successes, leading climate philanthropies recently announced a joint investment of $450 million to help catalyze a faster phase-down of non-CO2 super climate pollutants by helping national governments implement existing plans to phase-down super pollutants, catalyze ambitious economy-wide Nationally Determined Contributions (or NDCs) that incorporate all climate pollutants, and help leverage additional resources to triple climate finance on non-CO2 pollutants by the end of the decade. One of us (Ulman) runs a major climate foundation and it is clear that there is an immediate opportunity to address these more potent drivers of the challenge we are confronting. Speed must be a central metric for climate funding, along with scale, cost, and probability of success.

2023 officially the hottest year on record and best projections indicate that if the rate of warming continues to accelerate, as it has in the last two years, we will exhaust the budget for 1.5°C within this decade and 2°C by mid-century.

Every tenth of a degree of heating matters – especially to vulnerable people already feeling the impacts of climate extremes. This means that securing humanity’s collective future requires faster-acting strategies than have yet been widely adopted.

If philanthropy is to have the greatest impact, it is important to understand where we are now, how we got here, and what we can do next.

The threat from super climate pollutants

Carbon dioxide, the product of burning fossil fuels, contributes about 55% of current global warming from greenhouse gasses, and this has been the primary focus of most climate philanthropists.

However, scientists have long known that the other 45% of present-day warming comes from super climate pollutants, primarily methane (the main component of natural gas and also in emissions from cattle), ground level ozone (smog), fluorinated gasses (such as those in air conditioners), and nitrous oxide (a product of fertilizer and some industrial acids that stays in the atmosphere for about 112 years). Black carbon (soot) is not a greenhouse gas but another potent climate pollutant that is also an air pollutant as a primary constituent of fine particulate matter pollution (PM2.5), which is responsible for millions of premature deaths each year.

The short-lived climate pollutants—methane, ground-level ozone, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), and black carbon—are a subset of these super climate pollutants that are up to tens to thousands of times more potent in trapping heat than carbon dioxide, pound for pound. As their name suggests, they are also “short-lived”, typically remaining in the atmosphere for a few days to 15 years, as opposed to 300-1,000 years or more for carbon dioxide. Cutting them, therefore, can have a much more rapid effect, drastically slowing the rate of warming. As most of them are also air pollutants, this will also improve air quality, saving lives all over the world.

The United Nations’ most recent climate assessment recognized that “strong, rapid, and sustained reductions” in the short-lived super pollutants, alongside the multi-decade energy transition, is the best way to slow warming in the next crucial decades. Science is showing us how: in a recent publication for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, one of us (Dreyfus) describes an approach that targets the short-lived super climate pollutants for rapidly reducing warming, while continuing efforts to phase out fossil fuels as fast as possible. Indeed, encouraging progress is being made to cut many sources of these emissions. But, much more is needed.

Looking to recent history for inspiration and guidance

The 1987 Montreal Protocol has phased out nearly all the chemicals that were destroying the stratospheric ozone layer, which shields the planet from most of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation. Because these chemicals also caused significant warming, it has also achieved more than any other agreement to reduce climate change. The protocol’s success will avoid up to 1°C of warming by mid-century and up to 2.5°C by the end of the century. It has already delayed the onset of an Arctic summer without reflective sea ice by 15 years, preventing significant warming from occurring.

Building on this success – and with the backing of the philanthropic community – NGOs and small island nations successfully pushed for an amendment to the protocol to phasedown HFCs. This 2016 Kigali Amendment will avoid most of the 0.5 °C of warming these super pollutants would have caused by the end of the century. More recently, national governments, NGOs, and philanthropies have begun to come together to target methane through the 150-nation strong Global Methane Pledge.

Learning from–and leading by–example

There is much to be learned from the role philanthropy played in the passing of the Kigali Amendment and the establishment of the Global Methane Pledge. Climate philanthropists were instrumental in providing steady funding to the NGOs that helped create momentum for the Kigali Amendment, and also put together a fast-start fund of more than $50 million in 2016 to pull additional countries into the agreement. Similarly, philanthropy set up a $300 million fund, the Global Methane Hub, to help finance efforts to cut methane over the course of three years. Philanthropy has also stepped in to sponsor a study by the U.S. National Academies of Science to develop a research agenda for removing methane from the atmosphere.

It’s a great start, but there is a lot more to be done before our efforts start to slow warming. Accelerating Kigali’s initial schedule for phasing down HFCs, for example, would avoid an extra 0.1° C by 2050, which is comparable to the reductions from decarbonization in 2050, with much larger reductions from decarbonization later this century. And improving the energy efficiency of air conditioners and heat pumps at the same time as acting on HFC refrigerants could double the Kigali amendment’s benefit to climate. And the voluntary Global Methane Pledge needs to evolve into a muscular agreement with mandatory targets and timetables, along with a dedicated funding mechanism like the Montreal Protocol.

Philanthropy alone cannot make these changes, but it can help to catalyze the funding needed by helping to support the adoption of policies, such as all GHG inclusive nationally determined contributions, and international agreements that are needed to get these emissions sources under control. So, the question is, “What now?”

Optimizing for success

Climate philanthropy should be able to walk and chew gum at the same time: we can make necessary headway on the super climate pollutants while continuing to make progress to decarbonize the global economy. The key is to be clear about what we are optimizing for when facing the familiar challenges of prioritizing what organizations and efforts to support – and how to support them – and balancing portfolios with effective grantmaking frameworks to guide decision-making in the field.

Sequoia prioritizes a strategy’s speed – its potential to have impact by 2030 – and scale, targeting the biggest levers for transformative impact. Sequoia focuses on strategies, tactics, sectors, and geographies where our grantees can have the greatest impact in a short time. Since it also recognizes that its resources are dwarfed by the magnitude of the climate crisis, it aims to be cost efficient, making calculated and leveraged bets to get the most for our investments. Finally, it seeks to increase its probability of success by investing in evidence-based solutions that are likeliest to achieve near-term change.

Climate philanthropy has made some strides in thwarting near-term warming, but can have more impact by broadening its investments to include more strategies to reduce super climate pollutants. Of course, it cannot act alone. Significant funding is also needed from private and public sources, including the World Bank, which has demonstrated renewed interest in reducing methane emissions, and the International Monetary Fund, which completed its own methane analysis.

As the history outlined above demonstrates, and as we have argued elsewhere, philanthropy works best when partnered with others. Future agreements should align around the concerns of the global south, whose communities are often the most vulnerable to the worst impacts of climate change. Working with public and private entities around the world to prioritize near-term warming now will give our longer-term investments in decarbonization time to pay off — and give future generations a fighting chance of living in a cooler, healthier world.